11 Jul 2021, last revised 30 Oct 2025

Collecting, studying, and appreciating antique Copper Country bottles starts with being able to identify them. First, how do we know if a bottle is a Copper Country bottle? Simple. If the embossing states a local town name, it is a Copper Country bottle. If a bottle has embossing for the company name or proprietor(s) but not for the location, local history information is needed to determine its provenance. If a bottle is unembossed, we have no way of knowing who bottled it. Such a bottle would not be valued as a Copper Country bottle even though it may have been used by a local bottler. Unembossed bottles lack identity.

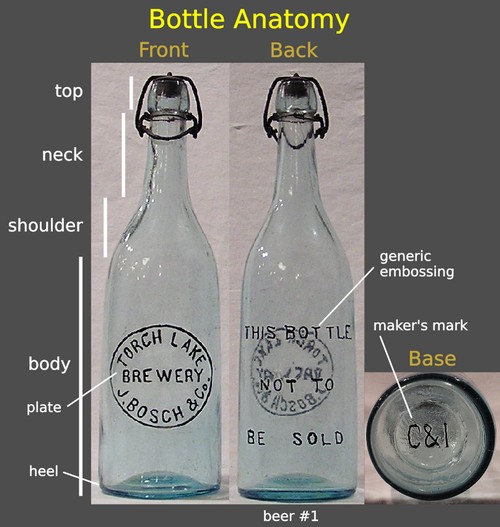

First, let's review the features of a bottle, using hand-blown Torch Lake Brewery #1 as an example.

Top: The top of the bottle was hand finished for a particular closure; in this case, a lightning stopper.

Molded Shape: Molten glass was blown into a mold to form the shape of the body, shoulders, and neck. This shape is characteristic of a particular type of bottle; in this case, a champagne beer bottle.

Plate: A plate was inserted into the mold to create signature embossing for the bottler. The embossing associates a bottle to a particular bottling company from a particular town. It gives the bottle an identity.

Maker's Mark: Some bottles are embossed with a mark from the bottle maker. These marks can be found on the base or the heel. In this case, we see the C & I mark on the base, which signifies that Cunninghams & Ihmsen of Pittsburgh, PA made this bottle.

Generic Embossing: Some bottles contain embossing notifying the customer that the bottle needed to be returned to the bottler. A common notice was THIS BOTTLE NOT TO BE SOLD. This is generic embossing because it was not particular to any bottler or bottle maker. It may be located on the back, base, or above the heel.

Other Marks: In some cases, particularly for soda bottles, the base contains initials, a monogram, or logo for the bottler. Some bottles also bear numeric or alphanumeric codes on the base or heel that may be factory and/or mold identification marks. A few bottle makers embossed a date code on their bottles.

Bottle Typing

Next, we may ask, how do we know what type of bottle we have? Or, likewise, what product did the bottle contain? Our scope for bottle typing is greatly simplified given that the Copper Country had primarily four types of bottles: beer, soda, pharmacy, and dairy. Again, we can reference the embossing. If a bottle states BREWERY or BREWING CO., we can rest assured that it contained beer and thus it is a beer bottle. If it states PHARMACY or DRUGGIST, we have a pharmacy bottle, and it most likely contained prescription medicine. Some dairy or milk bottles state DAIRY in its name, but others do not. You may then think soda bottles should state SODA on them, but none from the Copper Country do; although one used POP. Instead, soda bottles often have BOTTLING WORKS as part of their company name. Unfortunately, this only tells us that they bottled a beverage, not what type of beverage. In fact, Sanborn maps label the bottling building of a brewery as Bottling Works. When we do not have local history information to inform us, we need to resort to bottle typing based on bottle shape. Different closures and colors also accompany particular types.

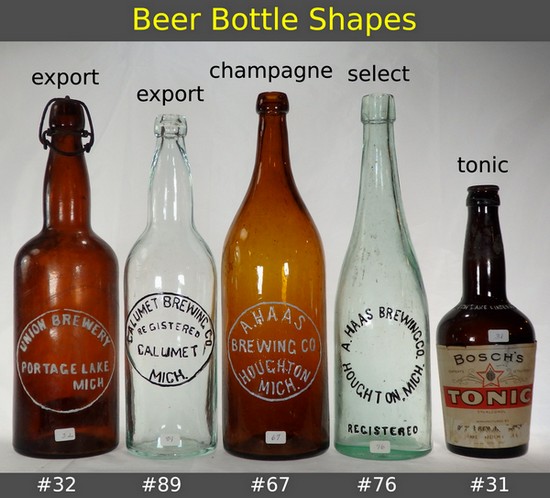

Beer Bottles: As listed in the Illinois Glass Co. 1906 catalog and the North Baltimore Bottle Glass Co. c.1900 catalog, beer bottles had several characteristic shapes: export, apollinaris, champagne, select, Weiss, and malt extract or tonic. For the Copper Country, we find mostly the champagne shape, with a few export, select, and tonic. The champagne has a classic bottle shape with tapered shoulders that smoothly transition from the neck to the body. The export is characterized with a swollen neck and sharply tapered shoulders. We find two styles of export, the classic more-slender form and an earlier fatter-bodied form. The select has a shorter body and taller shoulders that are continuous with the neck. The tonic has a swollen neck, like the export, but is short and squatty with a base narrower than the shoulders. The closures we find on Copper Country beers are the lightning stopper, Baltimore loop seal, cork seal, and crown cap. Most are amber in color but a few are aqua, colorless, or olive.

The standard sizes for beer bottles were quart and pint. As indicated by the catalogs, however, actual capacities were often lower (24-33 oz. for quart and 11-16 oz. for pint).

Soda Bottles: Copper Country soda bottles basically have a short-necked shape (for a Hutchinson or Twitchell marble stopper) or a long-necked shape (for a cork and wire, Baltimore loop seal, or crown cap). In contrast to beers, most Copper Country soda bottles are aqua in color, with a few being amber, colorless, or cobalt blue. Mold shape varied, especially for the quart-sized Hutchinsons, with some being narrower and taller while others being wider and shorter.

Some soda bottles contained mineral water. This is clearly the case for some of the bottles from Sterling Spring Mineral Water Co., Houghton Mineral Water Bottling Works, and Mountain Valley Water Co. However, because they used soda-type bottles, we catalog them with the soda companies.

The standard sizes for soda bottles were quart and half-pint. Actual capacities reported in the catalogs tended to be lower for the quart (26-32 oz.) and mostly accurate for the half-pint (8 oz.). Some soda molds had capacities of 10 - 15 oz. and the Copper Country has a few examples of such intermediate sizes (#77, 86, 144, s35). The Illinois Glass Co. 1906 catalog listed siphons in sizes of 18, 28, 37, and 44 oz., but the Copper Country siphons seem to be all 26 oz. (as marked on some bottles).

Beer vs. Soda Bottles: The long-necked soda bottles have a shape similar to the champagne beer bottles, but there are subtle differences. The quart crown top or Baltimore loop seal top soda bottle is narrower in diameter (3¼" vs. 3½") with a shorter body and longer neck than a typical champagne beer bottle. The half-pint crown top soda bottle is shorter with a shorter neck than a pint champagne beer bottle.

What confuses the distinction between soda bottles and beer bottles is that sometimes (but rarely) a soda bottle was used to bottle beer, or a beer bottle was used to bottle soda. What do we call them then? For example, N. & J. Bottling Works #88 is a quart bottle with a Hutchinson top but it has a long neck and squatty shape. This shape is pictured in the catalogs with the champagne beers, but N. & J. bottled soda. Thus, we identify it as a beer-type bottle but catalog it with the soda bottlers.

In other cases, we do not know based on bottle shape and embossing if the bottle contained beer, soda, or mineral water. These include Clifton Bottling Works (#121), Excelsior Bottling Works (#122, 123, and 124), and Red Jacket Bottling Works (#126). These bottles are amber, quart, and champagne-shaped with a Baltimore loop seal top, all the hallmarks of a typical beer bottle. But the embossing states, BOTTLING WORKS, which is a hallmark of soda bottles. Fortunately, local history information has determined that many of the bottles in the "Unknown Brewers and Bottlers" section of the bottle book were used by a beer agent; and thus, we classify them with the beers.

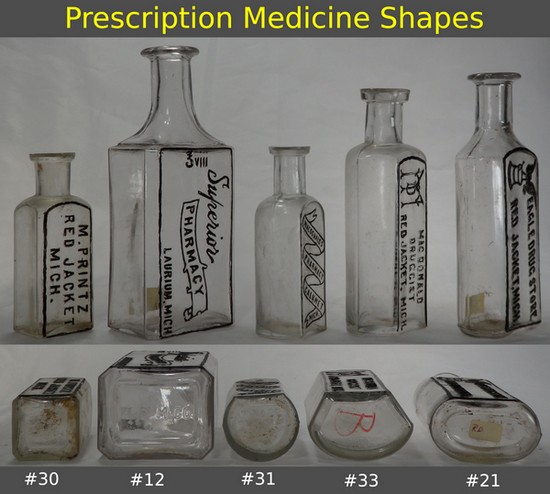

Pharmacy Bottles: The main type of bottle from a pharmacy was the prescription medicine bottle. While beer and soda bottles were cylindrical, prescription bottles had various cross-sectional shapes and shoulder styles, which make them more difficult to characterize as a whole. (They are classified in Pharmacy Bottle Styles below). Most had some type of oval shape with a flat panel. The outwardly tooled lip, called the prescription lip, with later ones being collared, is quite characteristic of prescription bottles.

Some pharmacy bottles were not prescription bottles, and these have their own characteristic shapes. Sodergren & Sodergren #17 was a nursing bottle, and it has a squatty oval shape with a bead finish. Geo. H. Nichols #7 was a citrate of magnesia bottle with a porcelain lightning stopper. Sodergren & Sodergren #18 and C. J. Soren & Co. #25 were ball-neck panel extract bottles with an extract lip. Despite the various shapes, all but one the Copper Country pharmacy bottles are colorless.

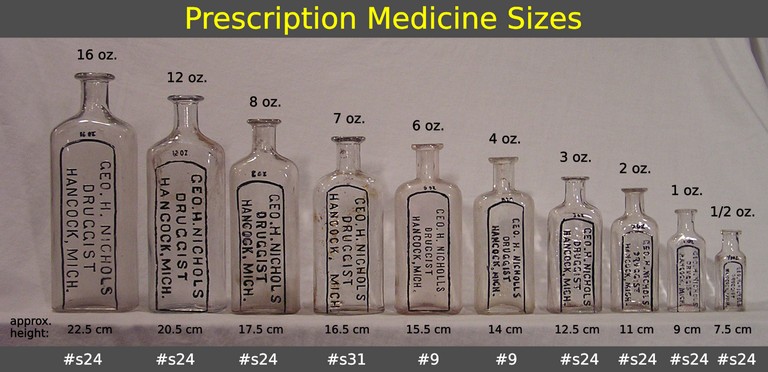

Prescription bottles came in sizes of ½ oz. to 32 oz., although we do not find the 32 oz. size for the Copper Country.

Pharmacy bottles were sold under given names for different shapes. Some shapes were patented, as sometimes indicated by patent dates embossed on the base. Some were signature types of a particular glass company, but not patented. Some were produced by various bottle makers because they presumably were not patented or the patent had expired after its 14-year lifespan. Lockhart et al. (1) noted that the patent date was unlikely embossed on the bottle after the patent had expired.

Distinguishing between bottle shapes is critical for identifying one pharmacy bottle from another. Different shapes can differ in base outline, body height, shoulder shape, or presence of graduated marks, a footed base, or a collared top. Here we categorize the shapes of Copper Country pharmacy bottles to aid in bottle identification. Note that some shapes have the same base outline (as illustrated) but differ in other features.

Ideal Citrate of Magnesia (16)

- cylindrical with long neck and porcelain lightning stopper

- made by Whitall Tatum Co. (16)

- found on #7

Nurser

- oval with tall shoulders and long neck

- sold by Dean Foster & Co. (8)

- found on #17

Millville Round (1)

- round with a flat face and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- patented by Whitall Tatum & Co. on 22 Jan 1878 (1)

- found on #31

Philadelphia Oval (3,16,17)

- oval with a flat face and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- introduced by Whitall Tatum & Co. in 1873 (19)

- found on #s31, s60, s73, s74, s75

Hollis Oval (20)

- like Philadelphia Oval but with sloped shoulders sharp or smooth to body

- sold by A. M. Foster. & Co.

- found on #16, 21, 23, 24, 36, s26, s36, s40

KLONDIKE Oval (6)

- elongated oval with footed base and sloped shoulders sharp to body

- KLONDIKE embossed on base

- designed by A. M. Foster & Co. (6)

- found on #10

unknown name

- like KLONDIKE Oval but without footed base

- sold by A. M. Foster & Co.

- found on #5 and 6

unknown name

- slightly wider with smaller panel than KLONDIKE Oval

- made by Whitney Glass Works

- found on #s25

Knickerbocker Oval (1)

- somewhat flattened sides and concaved shoulders

- patented by Whitall Tatum & Co. on 11 Dec 1894 (1)

- found on #11, s68

SHELDON Oval (9)

- like Knickerbocker Oval but with sloped shoulders sharp to body

- SHELDON embossed on base

- likely from Sheldon-Foster Glass Co. (9)

- found on #2

unknown name

- like Knickerbocker Oval but with rounded shoulders sharp to body

- sold by A. M. Foster & Co.

- found on #20, s79, s80

Eastlake Oval (8)

- wider than Knickerbocker Oval with rounded shoulders sharp to body

- sold by Dean, Foster & Co. (8)

- found on #3, s63, s69

Marion Oval (20)

- three flat sides and rounded shoulders sharp to body

- unknown maker

- found on #27

unknown name

- very slightly-curved back with rounded shoulders smooth to body

- sold by A. M. Foster & Co.

- found on #19

KELLOGG Oval (6)

- face and back flat with rounded sides and sloped shoulders smooth to body

- KELLOGG embossed on base

- designed by A. M. Foster & Co. (6)

- found on #s24

KELLOGG Oval (variant) (20)

- rounded shoulders smooth to body

- lacks the KELLOGG base mark

- sold by A. M. Foster & Co. or made by Whitall Tatum Co.

- found on #9, 14, 22, s56, s57

Windsor Oval (20)

- wider than KELLOGG Oval with rounded shoulders smooth to body

- sold by A. M. Foster & Co.

- found on #35

Double Philadelphia Oval (1)

- much wider than KELLOGG Oval with rounded shoulders smooth to body

- patented by Whitall Tatum & Co. on 07 May 1878 (1)

- also sold by A. M. Foster & Co.

- found on #s39, s71

unknown name

- like Double Philadelphia Oval but with sloped shoulders smooth to body

- unknown maker

- found on #s30

Baltimore Oval (2,3,5,14)

- four flat sides with rounded corners, side-straps, and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- made by Whitall Tatum & Co.

- found on #1, 26, 28, 32

Wizard Oval (14,18)

- chamfered front corners, curved back, flat sides, concaved and scalloped shoulders, collared top, and graduations

- sold by Western Bottle Mfg. Co. (14)

- found on #s23

unknown name

- like Wizard Oval but with concaved shoulders, non-collared top, and no graduations

- sold by Western Bottle Mfg. Co.

- found on #s72

unknown name

- fatter than O with strongly curved back and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- unknown maker

- found on #34

Chicago Oval (8)

- tapered, flat sides and flat or rounded shoulders

- patented by Adelbert M. Foster on 15 May 1888 (8)

- sold by Dean, Foster & Dawley and Dean, Foster & Co. (8)

- found on #4, 8, 33, s84

Duplex Oval (14)

- tapered, flat sides smoothly rounded to back with graduations and concaved shoulders

- sold by Western Bottle Mfg. Co.

- found on #s38

Monograph Square (5)

- square with rounded corners and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- unknown maker

- found on #s29

French Square (2,3,16,17)

- square with chamfered corners and rounded shoulders sharp to body

- patented by George W. Stoeckel in 1866 (19)

- popular from 1860s to early 1890s (2)

- made by several glass companies

- found on #29, 30

PARIS Square (6)

- short-rectangular with chamfered corners and concaved, terraced shoulders

- designed by Dean, Foster & Co., 1900 (6)

- sold by Western Bottle Mfg. Co.

- found on #12

Blake (3,16)

- like PARIS square but longer with flat shoulders

- made by Whitall Tatum Co.

- found on #s53

BREED Square (7)

- like Paris Square but with curved back

- designed by Western Bottle Mfg. Co. in 1901 (7)

- found on 15, s27, and s32

Sylvan Oval (5)

- like BREED Square but with tall body, graduations, and long, concaved shoulders

- sold by Western Bottle Mfg. Co.

- found on #13, s59

Argyle Panel (3)

- ball neck with extract lip and rounded shoulders smooth to body

- made by Sheldon-Foster Glass Co.

- found on #18, 25

Milk Bottles: The Common-Sense milk bottle, patented in 1889 and marketed by the Thatcher Mfg. Co. (10), became what is widely recognized as the standard milk bottle. It had cylindrical shape, gradually-tapered neck, and a wide mouth. The lip had a thick rim and an internal ledge (the cap-seat) for a milk cap. A few early milk bottles were hand-blown, but most milk bottles were machine-made with press-and-blow machines, which left a circular valve or ejection mark on the base (12). Many later milk bottles were machine-made with a blow-and-blow (Owens) machine (12).

Signature labels on early milk bottles were embossed (13). Enameled labels, called "pyroglazing" on milk bottles, first appeared on Thatcher milk bottles in 1934 (10).

In the mid-1940s, the square or rectangular shape became the dominant milk bottle shape (12).

Milk bottles from the early 1900s had three standard sizes: half-pint, pint, and quart. Some dairies from outside the Copper Country also had a quarter-pint, often used for cream (13). The half-gallon size gained popularity from the 1940s with the square- or rectangular-shaped, pyroglazed bottle.

Bottle Dating

Next, we might ask, how old is the bottle? It would have been simple if antique bottles came with a date, but very few makers dated their bottles. Instead, we can estimate a date range for a bottle by overlapping the different dimensions of bottle history: bottle making technology, bottle maker history, and local bottler history. We have explored the first two dimensions on separate pages (see Bottle Making and Bottle Closures for bottle making technology and Bottle Makers for bottle maker history). We present local bottler history on individual bottler pages. Recall that we explored the process of dating a bottle with S. & S. #2 as an example on the Bottle Making page.

Now let's use Torch Lake Brewery #1, featured for bottle anatomy on this page, as another example of dating a bottle. The key is to use the historical information to narrow the upper and lower limits of a date range. We know that Joseph Bosch started the brewery in 1874, and with partners formed Joseph Bosch & Co. in 1876. The firm became a stock company in 1894 under the name, Bosch Brewing Co. and finally closed in 1973. Because the bottle is embossed, J. BOSCH & Co., we can associate it to the company period of 1876-1894.

We see that the bottle had a lightning stopper, not only based on the shape of the top but also because the actual stopper was preserved. The lightning stopper was patented by Charles de Quillfeldt in 1875 and applied to beverage bottles in 1877 by Karl Hutter. Thus, we can constrain the lower limit of the date range to 1877. Another supporting piece of history is that lager beer was not successfully bottled until pasteurization was available. Louis Pasteur successfully pasteurized beer in 1870, but did not publish the result until 1877. Some brewers learned of Pasteur's experiment before he published and started bottling beer from the early 1870s. This apparently was not the case for Copper Country brewers, since if they had bottling prior to 1877, their bottles would not have had a lightning stopper.

Torch Lake Brewery #1 also has the C & I maker's mark. This mark is attributed to Cunninghams & Ihmsen, which was one iteration of a long history of Cunningham family companies. Based on company name changes, the C & I mark dates to 1865-1878. Thus, we can constrain the upper limit of the date range to 1878. Adding these pieces together, we date this bottle quite narrowly to 1877-1878. It should be noted, however, that when a glass company changed names and thus maker's marks, molds with the old mark may have been used until they wore out, instead of being immediately discarded (Lockhart et al.). It is unknown if this practice applies to C & I changing to C & Co., nor is it known how long a mold could last. It is a point to keep in mind when dating bottles using maker's marks from a company succession.

Bottle Cataloging

Collectors strive to obtain at least one example of each bottle. But what makes one bottle distinct from another?

Our Bottle Numbering System: We use the same numbers used by the book and expand upon its classification system. Obvious differences led to distinct bottles, which were given ID numbers. Differences in maker's marks of otherwise similar bottles were listed as bottle variants. Thus, for our classification system:

- Bottle ID Number: Assigned to a distinct bottle (e.g., beer #1). These are the same numbers used by the book. Beer, soda, pharmacy, and misc. each have their own set of numbers (e.g., there is a beer #1 and a soda #1).

- Supplemental (s) ID Number: Assigned to a distinct bottle not featured in the book (e.g., beer #s1). We use the same set of s-numbers for all types of bottles. The next bottle that is discovered and logged will receive the next number in the sequence.

- Suffix Letter: Assigned to a variant of a bottle (e.g., beer #1a).

- ABM Beers and Sodas: We start a new numbering sequence with "abm-" as a prefix (e.g., abm-1).

- Milks: We start a new numbering sequence with "m-" as a prefix (e.g., m-1). Most milks are ABMs but a few were hand blown.

Bottles are listed in presumed chronological order for each bottling company. Note that sometimes this order deviates from the chronological order of bottle ID numbers. As we learn more about the bottles, we will continue to revise the chronological order to better reflect the succession of bottles used by a bottler. Also note that most of the bottles we feature on this website have had their embossed labels painted for clearer photography.

Based on how mouth-blown, hand-finished bottles were made, we can expect some variation that does not necessarily signify different bottles. Specimens of the same bottle are expected to differ in height slightly due to inconsistencies in finishing the top. Thus, it is more important to examine shoulder height and not neck length or overall height. The shade of glass color can vary due to different pots of glass, or appear different if the glass differs in thickness. Clearly, if the embossing differs in lettering or the orientation of the lettering, we have distinct bottles. However, when a plate wore out, the bottler may have opted to purchase a replacement plate with identical design. Because plates were hand cut, the engraver could not prevent producing a replacement plate that differed slightly from the original. It takes close examination of how the letters align, the size and style of individual letters, the spacing between words, and presence or absence of punctuation to determine if plates were mimics of each other. We consider such mimics to be variants of the same bottle.

How do we distinguish between "distinct bottles" vs. "bottle variants"? The features to consider include mold shape, top and closure, plate size, plate position on mold, plate embossing, maker's mark, generic embossing, and glass color. Here are the guidelines we used following our assessment of the book.

Plate Embossing

- Bottles with plate embossing that differ in lettering or design are cataloged as distinct bottles.

- Here, Twin City Bottling Works #115 has LOUIS DECKER in the center and the town name compared to #116.

Mold Shapes

- Bottles with different mold shapes are cataloged as distinct bottles.

- Here, Torch Lake Brewery #2 has a taller body than #s2. Otherwise, they have the same plate, top, and maker.

Bottle Sizes

- Bottles of different sizes are cataloged as distinct bottles for sodas, beers, and milks; and listed under the same bottle for pharmacy.

- Here, National Bottling Works #59 is a half-pint while #58 is a quart.

- Different sizes will obviously have different molds and plates.

Tops and Closures

- Bottles with different tops for different closures are cataloged as distinct bottles.

- Here, Torch Lake Brewery #4 has a lightning stopper top while #7 has a Baltimore loop seal top. Otherwise, they have the same plate, mold shape, and no maker's mark.

Plate Shapes or Sizes

- Bottles with plates of different shapes or distinctly different sizes are cataloged as distinct bottles.

- Here, Jos. James Bottling Works #s15 has an oval plate while #83 has a round plate.

- Different plate shapes or sizes also required different molds.

Plate Position

- Bottles with the plate in a different position on the mold are cataloged as distinct bottles. This means the molds were different as well.

- Here, Calumet Bottling Works #123 has the plate lower on the mold than #122. The plates are also mimics.

Glass Colors

- Bottles with distinctly different colors are cataloged as distinct bottles.

- Here, Torch Lake Brewery #1a is aqua while #s2 is amber. Otherwise, they have the same plate, mold shape, top, and maker's mark.

Color Variants

- Bottles with different, but related colors but are otherwise the same or similar are cataloged as bottle variants.

- Here, Torch Lake Brewery #9 is amber while #9a is light olive green. Otherwise, they have the same plate, mold shape, top, and maker's mark.

- Colorless and aqua, or aqua and green would also be considered color variants.

Maker's Marks

- Bottles with different maker's mark but are otherwise the same or similar are cataloged as bottle variants.

- Here, Torch Lake Brewery #3 has the E. SON & H mark while #3a has the E S & H mark. Otherwise, they have the same plate, top, and mold shape.

- Usually, a different maker means the plate will be different, but in this case, the change in maker's mark represents a name change for the same glass operation.

Generic Embossing

- Bottles with vs. without generic embossing on the mold but are otherwise the same or similar are cataloged as bottle variants.

- Here, Bosch Brewing Co. #12a has REGISTERED while #12 does not. Otherwise, they have the same plate, top, and mold shape.

- Generic embossing on the plate, however, forms part of the plate design and warrants being distinct bottles.

- Note that the book catalogued a distinct bottle when generic embossing was on the front of the bottle, but not when on the back or base.

Bottle Rarity

Rarity is based on what has been discovered. Yet rarity is difficult to gauge without knowing the content of everyone's collections. Non-collectors may also possess a few antique Copper Country bottles with little knowledge about them.

For the bottle listings, we utilize the same rarity scale as the book.

- common = more than 50 specimens known

- scarce = 25 - 50 specimens known

- rare = 10 - 25 specimens known

- extremely rare = less than 10 specimens known

In some cases, shards indicate the existence of a bottle, but no whole example is known to exist.

We expect that more specimens of various bottles have been discovered since the publication of the book in 1978. Thus, the rarity scale may need to shift; however, it still functions as a relative assessment of rarity that can guide collectors.

Antique bottles represent a pioneering time of colonization, craftsmanship, and early innovation. They were used by local companies to serve local customers, before the age of automation and mass transport of people and goods. If you are fortunate enough to come across some of these antique bottles from the Copper Country, treasure them, as we may never again see local company and town names labeled on glass.

- Lockhart, B., P. Schulz, B. Schriever, B. Lindsey, C. Serr, and B. Brown. 2020. Whitall Tatum - Part I - Whitall Tatum & Co. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/WhitallTatum1.pdf

- Lindsey, B. accessed in 2021. Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. secure-sha.org/bottle/medicinal.htm

- Illinois Glass Co. 1906. Illustrated Catalogue and Price List. posted on Bill Lindsey's site.

- Putnam, H. E. 1965. Bottle Identification. Old Time Bottle Publishing Co. Salem, OR.

- Hochschild-Kelter Co. 1908. Catalog.

- Lockhart, B., B. Schriever, B. Lindsey, C. Serr, and B. Brown. 2013, revised 2021. A.M. Foster & Co. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/AMFoster.pdf

- Lockhart, B., B. Schriever, B. Lindsey, C. Serr, and B. Brown. 2020. Western Glass Mfg. Co. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/WesternBottle.pdf

- Lockhart, B., B. Schriever, B. Lindsey, and C. Serr. 2015. The Dean and Foster companies. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/DeanFoster.pdf

- Lockhart, B., B. Schriever, B. Lindsey, and C. Serr. 2019. The Sheldon-Foster Glass Co. and related companies. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/Sheldon-FosterGlass.pdf

- Lockhart, B., P. Schulz, C. Serr, B. Lindsey, and B. Brown. 2019. The Thatcher firms. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/ThatcherFirms.pdf

- Lindsey, B. accessed in 2022. Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. secure-sha.org/bottle/bases.htm

- Lindsey, B. accessed in 2024. Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. secure-sha.org/bottle/food.htm

- Lockhart, B. 2014. Milk Bottles and the El Paso Dairy Industry. published on: secure-sha.org/bottle/links.htm

- Lockhart, B. 2015. El Paso Prescription Bottles, the Drug Stores that Used Them and Other Non-Beverage Bottles. published on: secure-sha.org/bottle/links.htm

- Farnsworth, K. B. 2015. Drugstore Bottles for Archaeologists: Embossed Springfield Pharmacy Glassware from the Civil War to the Roaring Twenties. Illinois State Archaeological Survey. Technical Report No. 165.

- Whitall Tatum Company. 1913. Annual Price List - July 1, 1913. posted on Bill Lindsey's site.

- Whitall, Tatum & Co. 1886. Price List 1886. posted on Bill Lindsey's site.

- Illinois Glass Co. 1920. General Catalogue. posted on Bill Lindsey's site.

- Griffenhagen, G. and M. Bogard. 1999. History of Drug Containers and their Labels. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy. Madison, WI.

- Freeman, L. 1964. Grand Old American Bottles. Century House. Watkins Glen, N. Y.