05 Jun 2021, last revised 21 Feb 2024

Aside from the embossing, bottle collectors pay particular attention to a bottle's top. Examining the top reveals if a bottle was machine-made or mouth-blown, and if mouth-blown, whether the top was "applied" or "tooled" (see Bottle Making). In addition to the method of construction, the top had a specific shape for a specific closure (3), although some tops could accommodate more than one type of closure. Because the top and closure go hand-in-hand, usually only one is stated and the other is known or assumed to be known.

The Cork: Bottles of various types were traditionally sealed with a cork. The cork was used by Greeks and Romans from about 600 B.C. and gained common usage during the Renaissance (8). It is compressible yet elastic so it forms a tight fit even for irregular-shaped openings (8). Its cellular structure creates a lasting seal impenetrable by fluid or gas (8). We still see the cork today sealing most wine bottles, which is a testament to its utility.

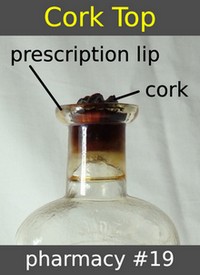

The cork was used to seal virtually all Copper Country pharmacy bottles. The top for these bottles consists of an outwardly tooled lip, called the prescription lip (10).

Beer, soda, and mineral water, however, presented a unique problem. Their contents were carbonated and the pressure could pop out a cork. Consequently, many closures were invented, patented, and utilized during the 1800s to solve this problem (8). The result is a fascinating history of innovative progression. We can observe this progression with the closures utilized by Copper Country bottles. Since some closures were particular to beers while others were particular to sodas, we can use the type of closure to help deduce bottle contents when little is known about the bottler. Since different closures were used during different time periods, we can also use the type of closure to approximate bottle age.

Putman Cork Retainer

The earliest top we find on Copper Country bottles is the blob top. The closure for this top consisted of a cork held down by a retainer (2,4). Several types of retainers were used from the early 1800s when soda and mineral water started to be bottled (1,2). But it was Henry Putnam's patent of 1859 that became the standard in the 1860s to early 1880s until it was superseded by the Hutchinson stopper (4). So, it is no surprise that Copper Country bottles with a blob top are recovered with the Putnam cork retainer. His closure consisted of a bail wire that held down the cork and a tie wire that secured the bail wire to the neck of the bottle (3). Based on the securing mechanism, we can see how the bulbous shape of the top was instrumental in preventing the tie wire from slipping off the bottle. To open the bottle, the bail was swung to the side and the cork was removed. This was a simple upgrade to the traditional practice of corking bottles.

The use of the term "blob top" has caused confusion because it only refers to the shape of the top and not the closure. The closure should be a cork and some type of retainer. Yet the specific type of retainer is rarely specified when someone says "blob top". Perhaps this is because the Putnam retainer is assumed, since it was the standard, or because the type of retainer is unknown, since it may not have been preserved with the bottle. Moreover, "blob top" should refer to only soda and mineral water bottles (1,2) since they are the ones that used the cork and retainer. Some may use "blob top" more generally to describe any top with a blobby shape. They may include other bulbous tops, such as the lightning top and the Hutchinson top, even though their closures lacked corks. Since these tops have their own characteristic shapes, they should not be called "blob top".

A soda bottle with a blob top typically has a stocky shape, and thus is called a squat soda. This characteristic bottle shape along with the top and closure allows us to deduce that the early Copper Country bottles were "soda bottles" even if the embossing does not specifically state so. It is unknown though if they all contained soda or if some contained mineral water. The broad distinction is that soda is artificially carbonated and flavored while mineral water is naturally carbonated and usually unflavored. Interestingly, one squat soda bottle was recovered with most of its contents. Its red color confirms that N. & J. bottled soda.

Hutchinson Stopper

In April 1879, Charles G. Hutchinson, the son of a Chicago bottler, W. H. Hutchinson, patented a stopper with a revolutionary design (1,3). The Hutchinson stopper was used from about 1880 to 1920 (3,4). It quickly replaced the blob top and its fastened-cork closure in the early 1880s (1,2), and was the predominate closure for soda from about 1885 to 1905 (3,4). A good number of Hutchinson bottles were produced for the Copper Country. Some are rarer than others, but all are valued for their unique shape and closure.

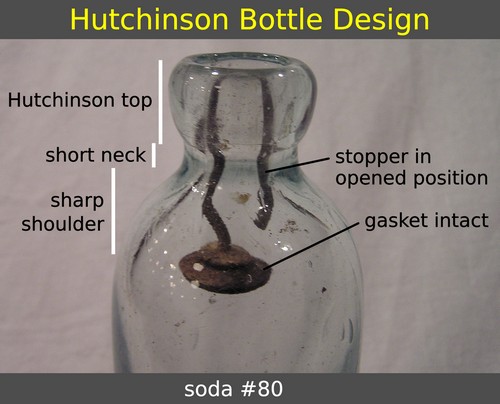

The stopper consisted of a rubber gasket held between two small metal plates (1,2). The metal plates were attached to a spring wire stem that was bend over to form a loop (1,2). The rubber gasket came in five sizes to accommodate different neck diameters, and the wire stem came in three lengths to accommodate different neck lengths (1). In 1890, W. H. Hutchinson & Son (Chicago, IL) sold these stoppers for $2.00 to $2.50 per gross (1).

The stopper was inserted into the bottle's top, which apparently was not an easy task (2), and the bottle was filled with soda. To form a seal, the stopper was pulled upward, with a foot-operated machine that hooked into the wire loop (2), so that the gasket formed a seal at the base of neck (1,2), and the wire loop protruded from the bottle's mouth (5) (see illustration on Bill Lindsey's page). The bottle could then be flipped over and back to produce internal pressure from carbonation to support the seal (1).

The bottle was opened with a sharp blow from the palm of the hand, which resulted in a loud pop sound as the carbonation pressure was released (2). Accordingly, it is commonly believed that the nickname, "soda pop" or simply "pop" originated with the Hutchinson stopper, but it actually originated with the blob top and cork closure (1). Locally, a newspaper announcement from 1869 for Shelden's "pop and soda works" (see J. L & B) and a newspaper ad from 1972-74 for Peter Bennie's "pop factory" (see B. & N) prove that "pop" was used prior to the invention of the Hutchinson stopper. Still, the Hutchinson stopper perpetuated the nickname (1), and the use of "pop" outlasted the use of the Hutchinson stopper. Even today "pop" is commonly used, especially in the Midwest to Northeast (6), despite the fact that soda bottles sealed with a crown cap (bottle cap) or twist top do not pop upon opening.

In the opened position, the length of the wire stem allowed the gasket to fall below the neck (2) while its inward curve held the stopper in the top of the bottle (3).

This stopper not only prompted bottle makers to produce a new shape of top, but it apparently required the bottle to have a very short neck and sharp shoulder (1). The end result was a very distinctive bottle shape that collectors easily recognize as a Hutchinson bottle.

So what was revolutionary about this design? Well in contrast to the cork which sealed the top, the Hutchinson stopper was an internal stopper that sealed at the base of the neck. Instead of opposing the pressure of carbonation like Putnam's retainer, it used the pressure to its advantage, to maintain the seal. It also required a new bottle shape that was strikingly different from the classic bottle. When this stopper became obsolete, so did its bottle shape. Some people today are at awe when they see such a funny looking bottle.

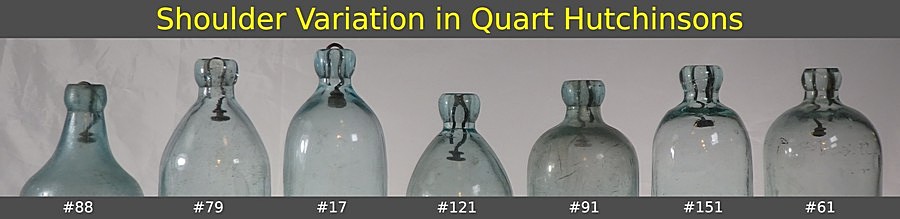

For this characteristic bottle shape, there was still variation among Hutchinson molds (3), especially early on and for the quart-size. Some bottles had shoulders that were more tapered, and these tended to be from the 1880s (2). In fact, Hutchinson's patent illustration featured a bottle with more tapered shoulders than what we see on later Hutchinson bottles. N. & J. #88 represents an extreme case of tapered shoulders. It is not recognizable as a Hutchinson bottle by its shape alone, but the few that were unearthed contained Hutchinson stoppers and the shape of the top matches other Hutchinson tops. Its maker's mark, C V G Co., indicates that it was produced in 1880, which would have made it among the first Hutchinson bottles produced nationally. It appears that the tapered-shoulder style quickly fell out of favor (2). Sharp, rounded shoulders presumably produced a better seal by allowing for more contact between the rubber gasket and the glass. We suspect the early N. & J. was an experimental bottle, one that probably failed to produce a strong seal.

A major criticism of the Hutchinson stopper was that it was unsanitary (2,3). Being an internal closure, there was space in the neck above the gasket that could collect dust (2). When the stopper was depressed, the dust contaminated the soda (2,4). Another problem was that the non-removable stopper made it difficult to properly clean the bottle between uses (2,3). Bottle diggers can attest to this, as they struggle to clean their latest finds without breaking the stopper. Its final downfall, though, resulted from competition with a superior closure, the crown cap, which slowly replaced Hutchinson bottles from about 1900 (3). In 1920, W. H. Hutchinson & Son stopped producing the stoppers (2). In the 1920s, all states adopted laws that banned the use of internal stoppers (which also included marble stoppers) because they were deemed unsanitary (1).

Twitchell Floating Ball Stopper

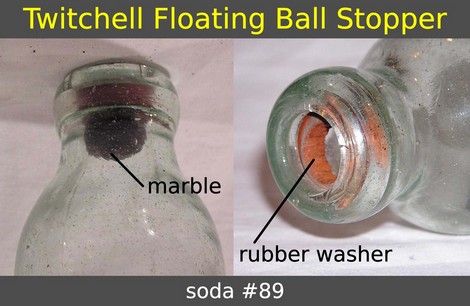

Despite a number of patents (2), bottles using a marble closure were oddities in the U.S. due to limited adoption. We are fortunate to have two examples from the Copper Country: Upper Peninsula Bottling Works #89 and Jos. James Bottling Works #90. These bottles utilized the Twitchell floating ball stopper, which was patented by William L. Roorbach in 1885 (4). This closure saw limited use in the mid- to late 1880s, mostly east of the Mississippi (3).

The stopper consisted of a hollow, floating composite marble or ball (4). The marble would form a seal when the internal pressure of carbonation held it against a heavy rubber washer situated in a double groove in the bottle's top (3). Curiously, the shape of the bottle resembles a Hutchinson bottle but with a wider neck to accommodate the marble.

Because this closure was rarely used, few references exist that describe its history. Graci (11) noted that floating ball stoppers were filled upright and then the ball "springs into position for closing by the action of carbonic acid gas in the beverage." Since it is unlikely that the ball jumped out of the surface of the soda, we presume the bottle was filled to capacity so that the ball could float high enough to contact the rubber washer. In contrast, Codd-type bottles used a glass marble. They were filled inverted and the glass marble would sink to the neck and form the seal (2). One clear advantage of a floating marble was that it would have floated to the bottom of the bottle when the bottle was inverted for drinking. Bottles with a glass marble needed to be designed with internal protuberances or grooves that could stop the marble from rolling down into the neck where it would have clogged the flow of soda (2).

Lightning Stopper

The age of bottling beer in the Copper Country started with the lightning stopper. This stopper was primarily used as a closure for beer (1). It was used nationally mostly from 1877 to 1910, and its variants still enjoy limited use to this day (3,4). In the Copper Country, it was used on the earliest beer bottles, from about 1877 to about 1890, before being replaced by the Baltimore loop seal. Furthermore, all Copper Country beer bottles with a lightning top have an applied finish. These beer bottles, due to their early age and rarity, are highly esteemed by local collectors.

The first patent of this toggle-type, lever-operated stopper was awarded to Charles de Quillfeldt of New York City in 1875 (1). Soon after its reissue in 1877, Quillfeldt sold the patent rights to Henry Putnam, who adapted it for fruit jars, and to Karl Hutter, who popularized it on beverage bottles (3,4). Others patented similar designs in subsequent years but their designs saw limited adoption (3).

Given the later patent dates, we see that beer was not bottled as early as soda, but yet the earliest Copper Country breweries started in the 1850s. These breweries clearly produced beer, but apparently did not bottle their beer until later. What changed? Well in the mid-1800s, lager beer became the most popular form of beer in the U.S., but this lighter, sparkling beer quickly spoiled (9). Louis Pasteur applied his pasteurization process to beer in 1870 and published the results in 1877 (9). With pasteurization, lager beer could then be bottled for transport and later consumption without spoilage.

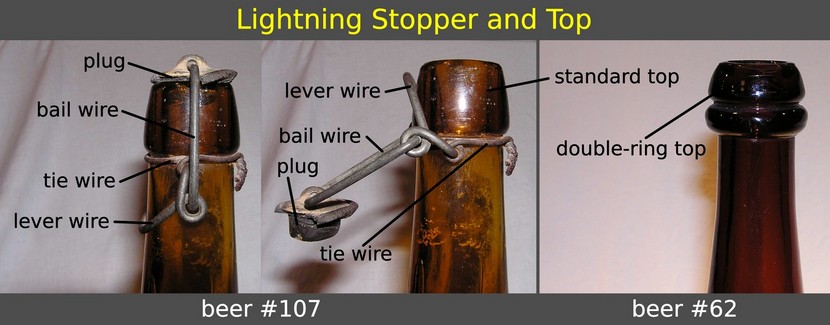

The original lightning stopper consisted of a rubber plug on a metal plate attached to a bail wire (1,5). The ends of the bail wire were looped around the loops of a lever wire (1). The lever wire was secured to the upper neck of the bottle by a smaller gauge tie wire (1). The loops served as fulcrums, and when the lever wire was depressed, the plug was pulled down over the bottle's mouth (1). The lever wire would then be secured against the bottle's neck after it passed its center of most tension (1). The rubber stopper came in various sizes to fit different-sized mouths (5).

The standard top for the lightning stopper was globular, which would have prevented the tie wire from slipping upward. A variation found in the Copper Country was the double-ring top used by A. Haas #62 and #63. This top is unusual because normally such a top used the groove to anchor a wire that retained a cork.

As for bottle shape, lightning-stoppered bottles had long necks, which makes sense since the lever wire needed to secure against the neck.

The lightning stopper did not require a specially-designed bottle for its use (3). It could be attached to any bottle that had a globular top and a long neck, such as bottles that previous used a cork (2,3) or later bottles with a crown top (3). It could be opened and closed quickly and repeatedly. It was the relative ease of attachment and operation that prompted the term "lightning" (2,3). It could seal carbonated or non-carbonated contents. In contrast, the Hutchinson stopper and marble stoppers required the pressure of carbonation to maintain the seal. The limitations of the lightning stopper were that it was relatively expensive to produce (1) and the wires would stretch and bend and needed to be replaced after several uses (5).

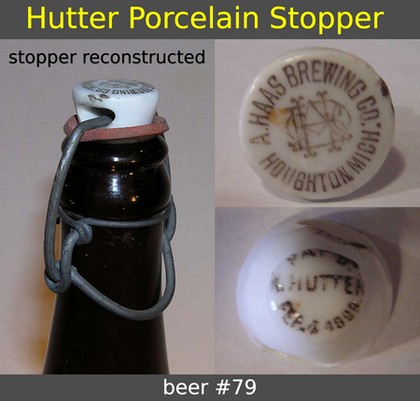

In 1893, Karl Hutter patented a lightning design that used a porcelain plug with a rubber seal (4). Usually these plugs contained no lettering, so it was fortunate that one for A. HAAS did. This stopper was most likely fitted on early crown top bottle #79 because a lightning-top bottle was evidently not produced by A. Haas after Hutter's patent date. Bosch #27 is another crown top beer that probably used Hutter's design. A porcelain lightning stopper was also used by the Nichols #7 pharmacy bottle.

Baltimore Loop Seal

For Copper Country beers, the lightning stopper was succeeded by the Baltimore loop seal, which was patented in 1885 by William Painter (3,4), a foreman of a Baltimore machine shop (5). This stopper was not typically used for soda (2) but Sterling Springs Mineral Water Co. used it on three of its quarts (#47, #48, #s44). The Baltimore loop seal quickly became the favored closure for beer (1) in Baltimore and the Midwest (4) because it was inexpensive to produce and easy to use (1). Strangely though, it was less common elsewhere (4), where the lightning stopper continued its reign (3). Von Mechow (4) commented that it "enjoyed moderate success, but was more popular in some areas than others." It turns out the Copper Country was one of the popular areas. The Baltimore loop seal was used on numerous Copper Country beer bottles from about 1888 to about 1912, and was slowly replaced by the crown cap from about 1900.

The Baltimore loop seal consisted of a rubber disc with a metal loop (5). The disc was fitted into a ring-shaped groove in the bottle's top, and the internal pressure of carbonation reinforced the seal (1). The stoppers cost $0.25 per gross (2).

When it was time to enjoy some locally brewed beer, the stopper could simply be pried off by hooking its metal loop (3). Because the stopper was inexpensive to produce, it was discarded after just one use (3,5).

Bottles needed to be specifically tooled to form the internal groove for the stopper. This characteristic groove makes it easy to identify a Baltimore loop seal bottle. The top, however, could be applied or tooled on any bottle shape since it did not rely on other parts of the bottle for the closure. We find a few examples of Copper Country beer bottles with the same plate and seemingly the same mold, but one has a Baltimore loop seal top and the other has a lightning stopper top. A bottler may have ordered both tops together during the transitional years to either try out the newer closure or to meet customer preferences.

Cork Seal

We see the return of the cork on post-1900 bottles containing premium beer (e.g., Gilt Edge from Bosch). These bottles were clear or aqua, probably to showcase the product, and all have a tooled finish. At least some of these bottles, if not all, had a metal wrap around the top that covered the cork.

These bottles had a more gradual shoulder taper than the typical beer bottle, and this shape is called a "select" beer bottle. This bottle shape also featured a Baltimore loop seal top or crown top.

Crown Cap

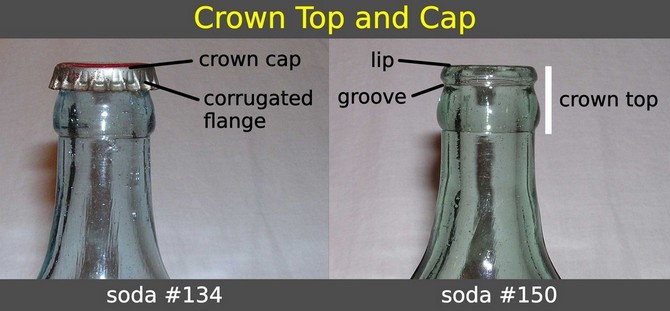

Having a different closure for beer vs. soda ended when a superior closure replaced them all. In 1892, William Painter patented what he called the crown cork (2). Today we know it as the crown cap or bottle cap. This thin-metal cap and its crown top should be familiar to everyone since it is still in use today. But back in the 1890s, few people probably could have imagined that it would become such a success. Up to this point, there were over 1,500 patents for bottle closures (7)!

The crown cap was a thin metal disc with a corrugated flange or shirt (3). On its underside, was a thin piece of cork, which formed a seal on the bottle's lip (3). Today, plastic is used instead of cork (3). The seal was maintained by crimping the flange around the bottle's lip and into a groove on the outside of the top (3). Painter stated that the cap "gives a crowning and beautiful effect to the bottle." (8). An article in the The Copper Country Evening News, 12 Dec 1896, p. 4 highlighted its innovation and noted that the Bosch Brewing Co. was an early adopter.

This closure was inexpensive (non-reusable), simple to install and remove (with an opener), and lacked the sanitary concerns like internal stoppers. Yet, it was not adopted so quickly for several reasons (1,3). Many people were initially in disbelief that such a frail lip grip could contain the powerful pressure of carbonation (2). In order to convince people, Painter shipped bottles of beer sealed with his cap from North America to South America (7). To people's surprise, it was still fresh on arrival (7). This closure required a new type of bottle top, and the top needed to be uniformly-made in order for the cap to fit securely (2). The bottler also needed new equipment for securing caps onto bottles (2). Because bottles were reused numerous times, a bottler that already had a good supply of Hutchinson bottles for soda or Baltimore loop seal bottles for beer might have been reluctant at first to order bottles in the new style and discard older equipment that was still perfectly functional (2). In addition, consumers may have preferred the older bottles that they were accustomed to for so long (2). Therefore, it was common for a bottler to have used both Hutchinson (or Baltimore loop seal) bottles and crown top bottles for an extended period (2). Some of these appeared to have been ordered together, as suggested by the use of the same, or very similar, plates on different molds with different tops (2). We have many examples of this practice from the Copper Country.

Some crown caps had custom labeling for the bottling company. Perhaps such a label was desirable since it allowed the company name (and flavor of the soda) to be visible from the top when bottles were packed in a case.

By 1905, the crown cap was gaining wide acceptance (5) and by 1920, all other closures were obsolete (3). It was Owens' automatic bottle-making machine, which was first licensed for soda and beer bottles in 1905, that perpetuated the success of the crown cap (1,2). Bottles could now be made easily and cheaply with standard specifications (1,2). The advent of machine-making, however, ended the tradition of mouth-blowing and hand-finishing that bottle collectors admire.

Although hand-finished crown top bottles may not be as appealing to collectors as the older and obsolete closures, they represent a short-lived transitional period between hand-made trade skills and machine-driven automation. Copper Country hand-finished crown tops were mostly used from about 1900 to 1915. They overlapped with Hutchinson and Baltimore loop seal bottles during about the first ten years of this period, and with machine-made crown top bottles during about the last five years of this period.

Some may argue that the crown cap no longer reigns king today, as it has largely been replaced in the last few decades by the screw cap. Unlike the crown cap, the screw cap does not require a bottle opener and it is resealable. Even glass bottles were largely replaced by metal cans, which now are being replaced by plastic bottles (and hence, the rise of the screw cap).

PRIOF Cap

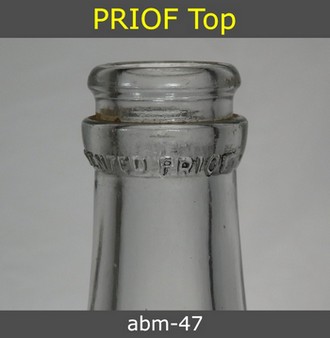

Innovation did not stop with the crown top despite its success. The PRIOF was a modification of the crown top, developed by the Illinois Glass Co. in the early 1920s (3). The top consisted of a ledge below the lip that functioned as a leverage point so that the cap could be pried off with any flat piece of metal. This design eliminated the need to have a dedicated bottle opener.

We find the PRIOF top on a few ABM soda bottles from the Copper Country. These bottles were made by the Illinois Glass Co., probably in the 1920s. The top appears to have a double-ring design, unlike the crown top. The ledge is embossed with REGISTERED PATENTED "PRIOF", making this top unmistakable.

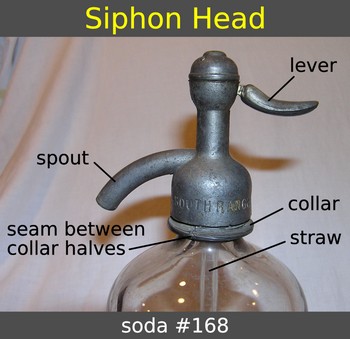

Siphon Head

The siphon was a specialty bottle for soda water or mineral water. The closure consisted of a pewter lever-operated dispensing head (2). A collar, formed by two semi-circular pieces, would secure under the bottle's top with a rubber washer. The rest of the head with a glass straw would then be screwed onto the collar. The bottles were filled inverted by forcing carbonated water under high pressure through the spout (2). They were filled to 150 psi while the bottles were made to withstand 200 psi (2). The Illinois Glass Co. 1906 catalog (posted on Bill Lindsey's site) stated, "Our Siphons are guaranteed to stand a pressure of 200 pounds (Standard Gauge), upon the first filling. After this proof of strength our responsibility ceases." (p. 233). Elliott and Gould (2) noted that the filler had to wear a protective face shield and coverings made of steel and leather in case of accidental explosion.

In order to withstand the high pressure, siphon bottles were made of thick, high-quality glass. They were commonly made in Germany, Austria, or Czechoslovakia (2,3). Siphons from the Copper Country, if marked, state, "MADE IN AUSTRIA". The labels were etched using a stencil (2). The glass was usually colorless (2,3), which is what we find for most Copper Country siphons.

Siphon bottles were expensive. The Illinois Glass Co. 1906 catalog listed a price of $0.85 each for the 44 oz. size, and stated, "Above prices include the cost of stamping heads and etching bottles with firm name, in lots of 100." For comparison, prices were not listed for beer and soda bottles because they needed to be quoted for particular specifications, but Elliot and Gould (2) stated that a gross of Hutchinson bottles cost $3.00 - $5.00.

Siphons had the advantage of being able to dispense a small amount of carbonated water without letting the rest to go flat (2). They were popular in saloons or for flavoring your own soda. They were refillable so they typically were not discarded unless broken (3).

Elliot and Gould (2) noted that earlier siphons had a footed base, but it was was prone to chipping; thus, later siphons used a plain base. Lindsey (3) dated the footed siphons to 1900-1920 and the plain-base siphons to mid-1910s and later. The Copper Country has both footed and plain-base siphons.

Milk - Ligneous Cap

Prior to the bottling of milk, a dairy wagon would deliver milk in large, metal containers (12). The milkman used a dipper to transfer milk from the container to a household pitcher (12). Dr. Hervey Thatcher, a druggist from Potsdam, NY, observed the unsanitary nature of this practice (12). Each time the container was opened, dirt from the street and hair from horses could fall into the container (12). Plus, the cream would rise to the top so the first deliveries received a surplus of cream, while the last deliveries received skim milk (12).

It is unclear when milk was first bottled (1), but the first patent for a milk bottle appeared in 1875 (12). In 1883, Thatcher patented a pail with a cover, known as the Milk Protector (1). In 1884, Thatcher invented a milk bottle, which was also known as the Thatcher Milk Protector (1). The first bottles used a nickel-plated cap with a lightning-type fastener (1). In 1886, Hervey D. Thatcher and Harvey P. Barhart patented a glass cap and wire bail closure (13). In the late 1880s and 1990s, other companies manufactured their own milk bottle, most having a lightning-type fastener (1).

The revolution in milk bottle design occurred when, in 1889, Thatcher's associates, Harvey P. Barnhart and Samuel L. Barnhart patented what Thatcher later advertised as the Common-Sense milk bottle (12). This is the standard milk bottle closure that collectors are familiar with. The wide top consisted of a thick, rounded ring with an internal ledge (the cap seat) onto which a wax-infused ligneous disk (the milk cap) would sit (12,13). The cap was disposable, making it easier to clean and reuse the bottle (12). Today, the bottles and the caps are both collectable.

Subsequent patents were issued for variations in the top of the cap-seat finish (13). The slogan roll (found on Twin Elm Dairy #m-58) had an embossed message on the lower edge of a common-sense finish (13). The syrup finish (found on Hillcrest Dairy bottles) had a thicker and taller top. The holdfast grip finish (found on Murtomaki #m-40) had ridges around the lower edge of the common-sense finish to provide better grip (13). Later common-sense finishes were greatly reduced in thickness (13), and we find them on later milk bottles with a square or rectangular shape and pyroglazed label.

After the ligneous cap sealed the bottle, a hood was often used to cover the top of the bottle (13).

Milk - Aluminum Caps

Later designs involved an aluminum cap that covered the top and secured on the outside of the finish. This cap was used in combination with a ligneous cap as a second layer of protection or as a seal by itself (13). Only two designs are found on Copper Country milk bottles.

The Econopor finish was slimmer and had only one size of downward projections around the lower edge of the finish (13). The aluminum cap secured on the projections (13). This finish was made with or without the cap seat, and with or without a bumper roll, which was a ring below the finish (13). We find this finish on later milk bottles with a square or rectangular shape.

Harvey Coale patented the Dacro finish in 1911, which was an adaptation of the crown finish used on soda and beer bottles (13). It had a ring on top to seal the cap and a reinforcing ring below (13). The cap was basically a large crown cap (13). We find this finish on Riverview Dairy bottles.

- Munsey, C. 1970. The Illustrated Guide to Collecting Bottles. Hawthorn Books, Inc. NY.

- Elliott, R. R. and S. C. Gould. 1988. Hawaiian Bottles of Long Ago: A Little of Hawaii's Past (revised edition). Hawaiian Services, Inc. Honolulu, HI.

- Lindsey, B. accessed in 2007, 2021, 2022. Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. secure-sha.org/bottle/closures.htm

- von Mechow, T. accessed 2007, 2021. Soda & Beer Bottles of North America. http://www.sodasandbeers.com

- Copper Country Bottle Collectors. 1978. Old Copper Country Bottles of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. F. A. Weber & Sons, Inc. Park Falls, WI.

- McConchie, A. accessed in 2021. Pop vs. Soda. popvssoda.com

- anonymous. accessed in 2007. Who Invented the Crown Cap Lifter? www.bullworks.net/virtual/infopages/crowncork.htm

- Lief, A. 1962. A Closeup of Closures. Glass Container Manufacturers Institute. NY.

- Lockhart, B. 2007. The origins and life of the export beer bottle. Bottles and Extras. May-June 2007: 49-58.

- Illinois Glass Co. 1906. Illustrated Catalogue and Price List. posted on Billy Lindsey's site.

- Graci, D. 2003. Soda and Beer Bottle Closures 1850 - 1910. self-published.

- Lockhart, B., P. Schulz, C. Serr, B. Lindsey, and B. Brown. 2019. The Thatcher firms. In: Encyclopedia of Manufacturer's Marks on Historic Bottles. posted on Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website. https://secure-sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/ThatcherFirms.pdf

- Lockhart, B. 2014. Milk Bottles and the El Paso Dairy Industry. published on: secure-sha.org/bottle/links.htm